Police use of force is certainly a popular topic these days, and a source of criticism when that force is perceived to be excessive or unnecessary. There have been plenty of examples of excessive and unjustified force in the news cycle over the past few years; along with a lot of examples of justified use of force that are unjustly decried because of the public discourse surrounding police brutality we are currently experiencing.

But what exactly is justified or necessary; and what is excessive and unnecessary? Let’s look at how police officers are trained in use of force.

(Please note: While what I’m going to talk about is more or less standard across the US, my training came at the hands of the State of Georgia; and will reflect the laws of that state. I am also by no means an attorney or qualified to offer any sort of source of legal wisdom; so none of this is to considered legal advice of any kind. Or any kind of advice; period- honestly, I’m a hot mess; anyone who takes my advice is gonna be disappointed. Also, I have not been active in Law Enforcement for 10 years now, and terminology has no doubt changed.)

First and foremost, any use of force is about one thing: Control. The police officer or sheriff’s deputy is trying to exert a level of control over the scene and the people in it. The need for control may or may not be justified; but to use force is to exert control, usually over a person. Our Courts have established some level of control by police is necessary, to preserve the life and safety of all involved, to determine the facts of the crime committed, and to bring the persons who committed the crime to answer for it. This isn’t a blanket license for law enforcement to exert total control over everyone they encounter, however; constitutional rights limit and guide what control is allowed and when. However, this essay is strictly about what use of force is, and what it entails. Believe me, reams and reams of paper have been written on this topic, and it is subject to constant wrangling in courts of law- as it should be.

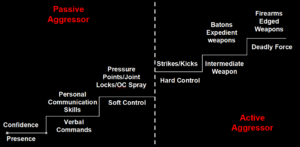

Use of force is a very fluid, very dynamic situation. Moving from just showing up to a scene and then ending up putting some guy in a joint lock may happen gradually, or it might happen immediately, depending on the situation. The force used will generally flow from one level to another, and possibly back down again. Rarely is it a formal, set series of steps in a predictable order… but that’s how it’s been portrayed in training sessions for decades. It might be given a fancy name like the “Integrated Force Model”, complete with impressive jargon; but, honestly, it’s the same stair-step diagram, and it looks like this fancy IFM diagram. Compliant subject on the left, cooperative controls by the officer on the right; stepping up to Assaultive, serious bodily harm or death by the subject, use of deadly force by the officer.

The simpler model, the one I learned back in the 90s, looked like a staircase, with mere Officer Presence at the bottom, and Deadly Force once again at the top.

No matter how you look at it, the concept is simple: you match your force with the level of resistance given by the subject; or one step above. You don’t have to start at the bottom and work your way up- if the subject is swinging a bat at your face, you’re not going to start with “Sir, please don’t”; that would be stupid. And, you can- and should– move both up and down this continuum as their resistance changes.

In fact, de-escalation should be your goal; to resolve this incident with the absolute minimum use of force necessary. It may start out looking like it’s gonna be a knock-down, drag-out, knuckle-duster of a brawl; until someone de-escalates and ends up just being some harsh words and later apologies. Ego and macho have no place here.

Except Deadly Force. You never jump to that one without meeting some specific criteria. But more on that later.

So, let’s match the levels of resistance with the levels of force.

Lowest on the scale is compliant subject, matched by officer presence and verbal commands. This guy is cooperating based solely on the fact that you are a LEO. The best situation, and it’s gained by your presence and your communication skills.

But let’s think about that presence. The middle ground is Officer Dogood Squarejaw, who steps from his gleaming cruiser with his hair perfect, his shoes and leather gear polished to a high gleam, his uniform immaculately creased. He approaches calmly and confidently, and when he speaks his voice is calm and comforting. What sort of reception do you think he’ll get?

Well, almost anything, really; the subject could be in any state of mind. But without even saying a word, he radiates competence and confidence, his body language speaks of his legal authority but not in an overbearing, authoritarian manner. He’s much more likely to gain compliance, or de-escalation, just by his presence alone.

What about Slobheart McCheesedoodle? The guy that leans heavily on the door when he gets out, uniform smudged with grease marks and bits of fried chicken, who smacks his baton in his palm as he approaches?

Well. The subject is probably gonna think he can get the better of this tub of shit, and he’s probably right. Even if he isn’t thinking of escalating just because he can, he certainly isn’t going to believe he’s going to get any help from this guy; and Slobheart’s attitude will probably match his appearance.

Then there’s Chad Tactical, who leaps from his cruiser festooned with black tactical gear and immediately begins asserting his authority. This is an escalation in action, without any words having been spoken. Multiplied if there other officers of his ilk swaggering their way onto the scene. And, sadly, there are a lot of Chads these days.

In other words, just because “Officer Presence” is at the bottom of the continuum, it doesn’t mean it can’t have an outsized effect on how the rest of the encounter turns out.

Next up are Verbal Commands, and Passive Resistance. Simply put, this is the uncooperative but not actively resisting subject; and verbal commands are… well, just that. “Place your hands behind your back”. And, of course, how these commands are given- volume, phrasing, tone- can have a great impact on whether or not this situation escalates or de-escalates. Shouting in “command voice” at the wrong time can be just as bad as lackadaisically suggesting that he, you know, put his hands up; if it’s not too much trouble. And it often works in concert with that officer presence mentioned before.

But what if verbal commands don’t work; and the guy continues his passive resistance? You may have to move up the continuum another step- physically move this person, or get them to unclench from the steering wheel. No, no; not whack a baton across his knuckles; that’s three steps above where we are, Mr. Trigger-Happy. Back off.

(Quick story time, because cops love to tell “war stories” to illustrate some point or another. Second agency, short, unassuming deputy we all called “Gunny” because he had been one in Vietnam. Much older guy, perhaps 5 foot 6, grey flattop, very soft spoken and gentle. But he had seen quite a bit in his day; according to stories others had told- he himself never spoke of Vietnam- he should have won the medal of honor for rescuing other soldiers while seriously wounded himself. You’d never know it by talking to him.

But I watched him talk down a guy 6 foot 3, drunk, and very angry; who swore if got out of these handcuffs he’d kick all our asses, and was trying his hardest to do just that. He was gonna be a real bitch to get in the back of the car, handcuffed or not.

Gunny walked very calmly up to him, put one hand on his back, and whispered in his ear, having to stand on tip-toes to do so..

The guy immediately stopped struggling. “We’re not gonna have any problems on the way to the jail, are we?” Gunny asked softly. “No, sir” the man said, and proceeded to calmly seat himself in the back.

Gunny never did say what he whispered in the man’s ear, but, small and unassuming as he was, he could always de-escalate a situation.)

Storytime over, back to standing on your heads. Active Resistance– the subject is actively trying to pull away or resist; but short of trying to land blows. This is met with “Soft Hands” techniques; usually in the form of pain compliance- joint manipulation, pressure points, etc; or less-lethal devices such as OC spray or TASER.

Whoa, whoa! You cry. Pain compliance? What medieaval torture crap is this!?

Well, until we invent a Star-Trek stun setting on our firearms, it’s all we got. And, frankly, for a great number of people, pain is an effective motivator. You perform an action and it causes you pain, you stop doing it; for fear of injury to yourself. But, this person isn’t actively trying to harm you; they’re just actively resisting you. We’re assuming you are justified in controlling them; so… how? With methods least likely to cause them injury?

Joint Manipulation is exactly what it sound like- manipulating joints in such a way as to either immobilize them or hyperextend them to the point of causing pain (but not far enough to cause injury, if done correctly). Pressure Points are nerve clusters that pressure can be applied to to cause pain, and hopefully stop the person from resisting. Mandibular nerve, infraorbital nerve, hypoglossal, clavical notch… all places pressure can be applied and produce pain.

What about OC and TASER? Well, because they are unlikely to- not impossible to- cause death or injury, they fall at this level. And on paper, they seem ideal- relatively high level of compliance with very little risk of injury to subject or officer? Hell yeah; sign me up! But, as we’ve seen, there are no magic bullets. I won’t say much more about them here as they are subjects of an essay in their own right, with a lot of nuances. And one thing to remember here is that once the resistance stops- so does the use of force. Continuing to arm-bar someone who isn’t resisting is excessive use of force; as is jumping up the continuum when the subject’s actions don’t warrant it.

Whoops- now the guy is assaultive; and trying to punch, kick, and hit you. Now the soft-hands gloves come off (or on, if you’ve got lead filled sap gloves; that are a step above this as impact weapons, and are banned by most all police agencies… or should be.) This active assault may be met with strikes of your own… or various impact weapons such as ASP Batons or “less lethal” impact rounds such as super-sock munitions or so-called “rubber bullets”, if the subject is also employing impact weapons. BUT- you must realize that you are now getting very close to lethal force; as these weapons have a much greater chance of causing serious injury or even death if they are misused… which we have all seen before, especially lately. These “hard hands” techniques are used when the attacker could cause bodily harm, but not great bodily harm. What is great bodily harm? “Visible bodily harm” involves visible injuries- bruises, cuts, etc- while “great bodily harm” is more serious- “injury to another person which deprives him or her of a member of his or her body, renders a member of his or her body useless, seriously disfigures his or her body or a member thereof, or causes organic brain damage which renders his or her body or any member thereof useless.”… in other words, the type of injuries likely to occur when impact weapons are used improperly; and the difference between the two may be the difference between hitting someone on the thigh or hitting them in the sternum.

Which brings us to Deadly Force; which, as you might expect, is described in deliberate terms.

OCGA 16-3-21a:

A person is justified in threatening or using force against another when and to the extent that he or she reasonably believes that such threat or force is necessary to defend himself or herself or a third person against such other’s imminent use of unlawful force; however, except as provided in Code Section 16-3-23, a person is justified in using force which is intended or likely to cause death or great bodily harm only if he or she reasonably believes that such force is necessary to prevent death or great bodily injury to himself or herself or a third person or to prevent the commission of a forcible felony.

A forcible felony, by the way, is armed robbery, rape, etc.

Well, that seems pretty clear; doesn’t it? Not much wiggle room there.

…Welllll, except for the words “reasonably believes”. What is reasonable? There is some “guidance” in case law with Graham v Connor, but… well… it starts to get very complicated again. In this first part, I’m just going to explain what the law is; in the second part, we’ll look at how it gets complicated.

Graham v Connor, in a nutshell, says that any use of force must be viewed in the lens of what a “reasonable” officer would have used; the force must be reasonable necessary when viewed by an officer of the same experience based on the totality of the circumstances. This is about the extent of the training cops are given on Graham v Connor; a simple paragraph that’s glossed over and usually a question on an Academy exam:

25: “What case established the Reasonableness Doctrine with regards to use of force?

A: Eugene v Debs

B: Graham v Connor

C: Tennessee v Garner

D: Terry v Ohio

But the background of the case, the make-up of the Supreme Court at the time, the numerous back-and-forth cases both before and after it… they all play a part. Which is why they’re in Part 2.

A good shorthand for judging such use of force, and taught in the Academy- and endlessly debated on internet forums- is Ability, Opportunity, and Jeopardy. As in, did the assailant have the Ability to cause death or great bodily harm; the Opportunity to do so, and was I in imminent Jeopardy of receiving the same?

Let’s say you’re standing on the corner of a very busy 6-lane street. On the opposite corner is a big, burly, 6 foot 5, 280 pound bruiser in a stained wifebeater staring straight at you, brandishing a switchblade and yelling “I’m gonna cut you wide and deep, boy”! Does this scenario meet AOJ?

Well, he certainly looks like he has the ability to gut me like a fish. However, he doesn’t have the Opportunity to do so… he’ll be run over six times before he gets across one lane of traffic. And I’m

not in imminent jeopardy of that; so, no… deadly force is not justified here.

Now, what if that same guy is standing right next to you, but he’s calmly cleaning his fingernails with the knife and haven’t said anything threatening to you, or even acknowledged your presence? Well, he still has the Ability; and all he has to do is turn and stick you, so he has the Opportunity…. but you are not in imminent jeopardy. Should he turn to you and tell you to meet your maker; well, then, all three are met.

There is a fourth leg to that stool that comes and goes in Law Enforcement training depending on the era; and that is Preclusion: the idea that deadly force is the only answer to protect yourself, and that all other options have been exhausted. Is there anything you could have done in that moment to avoid using deadly force without being hurt yourself? For example, if a robber says “Give me your money or I’ll hurt you”, is giving him the money a viable option? Unless you have some reason to believe he’ll hurt you regardless; then yes, it is. What about a car driving deliberately towards you? Is the better course of action to get out of it’s way? (hint: yes, yes it is. Because even if you hit that ol’ medulla with a perfect cranial vault shot, your bullet won’t stop that car, and you’ll wish you had spent your time getting out of the way instead of believing what movies told you.)

“Preclusion”, when it was introduced, was met with moans and groans from the LE audiences I taught. As for the reason why Preclusion has gone in and out of favor, well… just look at all the “stand your ground” lately.

So, there it is… what use of force is, and how it’s taught to Law Enforcement. Again, until we invent a way to safely and harmlessly incapacitate another person so that they cannot inflict harm on another, policing will always involve some use of force in order to control… the person, or the situation. The real question is in what is reasonable and necessary, and what is excessive.

But before we move on to Part 2, and take a more nuanced look, let’s add another, more human element to this dry, classroom explanation; and one that results in a lot of excessive force: Fear.

Fear is a system overload stimulated by the perception of danger or threat.

Fear is an emotional response to perceived danger or threat.

Fear is an autonomic emotional response to a perceived threat/danger.

Fear is an alarmed response that is characterized by a high negative effect (or emotion) and arousal.

Fear may be reasonable- that huge guy with the switchblade is a reasonable threat; hell, I’m afraid of him. I’d be afraid of him even without the knife; he’s got 5 inches and 60 pounds on me. The fear becomes unreasonable when, in scenario 2 of our little AOJ exercise, I whip out a gun and start blasting.

Fear can also be unreasonable right from the get-go, when you perceive a threat that doesn’t exist; from racial, cultural, or societal differences. Fear of a black man, based on stereotypes that have you believing that any black guy on a street corner wants to rob you. Fear of a Muslim, because you’ve been told they’re all jihadists looking to blow something up. Fear of that panhandler, because those filthy beggars will stoop to nothing to get your money. Other fears, such as fear that your training and skill isn’t up to the task. Fear of not being accepted by your peers, who may use excessive force because they can and they get away with it.

And let’s face it, there’s a lot of fear in this country right now.