Current Location: Home : Firearms : Juuhoukata Chap. 2-7

Chapter 2: Terminology

Terminal Ballistics

This topic is of great concern to both you and the target. A bullet that completely penetrates its target with a good deal of leftover energy will endanger anything behind the target. One that doesn't penetrate deeply enough might not stop the target. The factors that affect terminal ballistics are the material the target is made of, the energy of the projectile (a factor of weight and speed) and the design of the bullet. Since we will, however regrettably, be dealing with humans as a targets; we will concentrate on how bullets react when fired into bodies.

One large misconception is that big rounds, like the .45 auto, will knock the target on it's posterior. The .45 auto does indeed possess a lot of power, but nowhere near enough to knock a person over. Hollywood has made the image of the bad guy flying ten feet through the air after being shot a popular one, but it's simply not true. "Knockdown" capability is not a factor to be considered. "Stopping power" is, but this is a slippery term to define. It can be loosely defined as the ability of a given round to immediately stop the aggressive actions of another.

Another fallacy is that a certain round will stop a target every time. Terminal ballistics is not an exact science. There are so many factors present affecting the path of a bullet and how a target will react when shot that there is no way to predict with certainty what a target will do. There are cases of subjects shot multiple times with magnum calibers, in the head and chest, who remained alive and fighting for several minutes; and still others who survive. Again, there are people who are shot with a .22 rimfire who die instantly. There are things you can do to put the odds on your side; but there is no way to say "this shot will instantly stop the target". People vary widely in their ability to handle injury and pain, and when added to the vagaries of shot placement, bullet expansion, and many other factors, it becomes impossible to predict how someone will react to being shot.

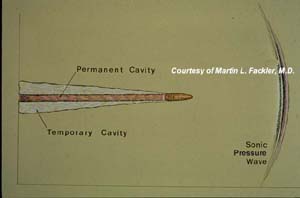

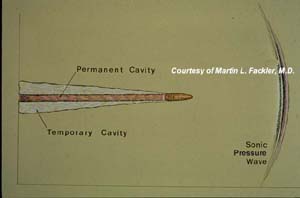

At left is a figure showing the typical path of a hollowpoint bullet through ballistic gelatin; a substance used in this sort of testing for its resemblance to human tissues. You can see that shortly after the bullet enters the gelatin, it begins to expand and creates several cavities. The first is the bullet track itself; a hollow tube created by the bullet. Fragments of the bullet also create fragmentation cavities, but these are usually very small. There is increasing evidence, however, that fragmentation damage plays a significant part in wounding potential. A temporary cavity is formed when the shock of the bullet entering the material forces a large stretched cavity that rebounds shortly after the projectile passes through. The permanent cavity is the hollow space that was once filled with material that the bullet has disintegrated with its passage. There is also a shock wave transmitted through the body from the bullet.

At left is a figure showing the typical path of a hollowpoint bullet through ballistic gelatin; a substance used in this sort of testing for its resemblance to human tissues. You can see that shortly after the bullet enters the gelatin, it begins to expand and creates several cavities. The first is the bullet track itself; a hollow tube created by the bullet. Fragments of the bullet also create fragmentation cavities, but these are usually very small. There is increasing evidence, however, that fragmentation damage plays a significant part in wounding potential. A temporary cavity is formed when the shock of the bullet entering the material forces a large stretched cavity that rebounds shortly after the projectile passes through. The permanent cavity is the hollow space that was once filled with material that the bullet has disintegrated with its passage. There is also a shock wave transmitted through the body from the bullet.

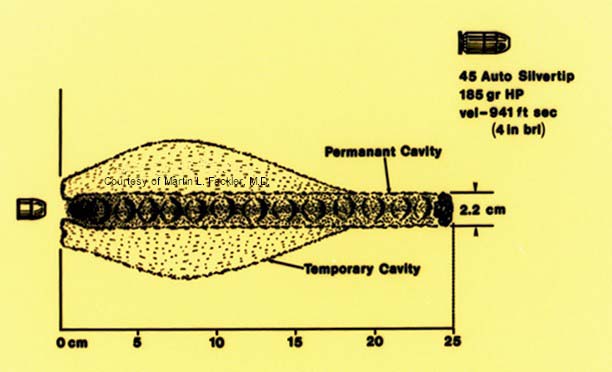

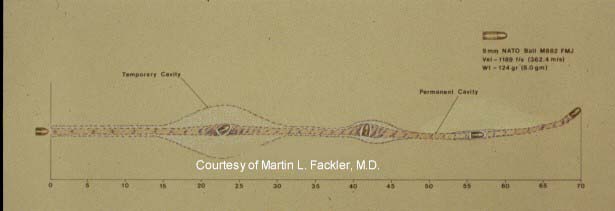

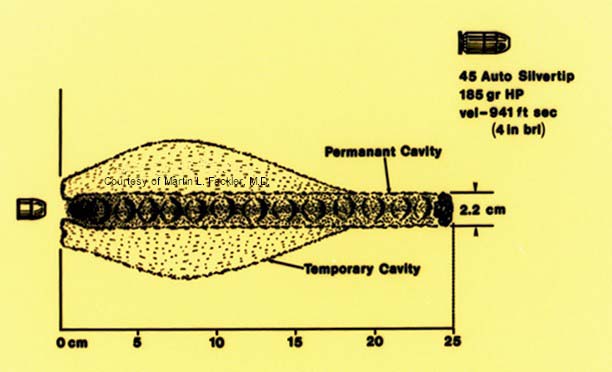

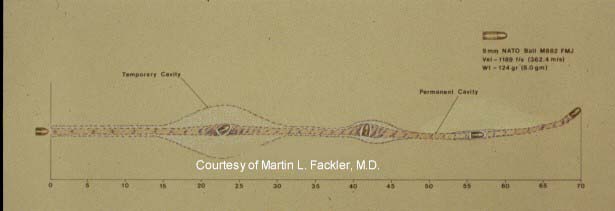

Comparing the two figures at the bottom of the page, you see that non-expanding bullets create very small temporary and very long permanent cavities; while expanding projectiles produce large temporary cavities and shorter, less penetrating permanent ones. The cavities are made by the energy that the projectile carries with it being dumped into the target. Death results from damage done to major organs, from the destruction of tissue found in the permanent wound channel and the tearing of structures pushed violently out of the way of the temporary cavity; from shock; and from blood loss.

|

At left is the wound channel for a .45ACP Winchester Silvertip. Note the shorter permanent cavity, as the bullet transfers energy to the surrounding tissue quickly and stops quickly. There is a substantial temporary cavity as well.

|

|

At right is the wound channel for a 9mm NATO hardball round, which does not expand. Note that the bullet travels a long way, and the only temporary cavities formed are from the bullet tumbling inside the body.

|

|

There is a great deal of controversy surrounded exactly what causes death from handgun wounds, and how bullets should be designed to exploit this. Gun magazines abound with pseudo-scientific claims of hydrostatic shock, central nervous system shutdown, and more. One camp relies on statistical data gathered from hundreds of actual shootings, another relies on scientific studies of wound channels in cadavers and ballistic gelatin. Ammunition manufacturers hype their products as being superior to the other guy's, and will use whatever data will support their claim. All you really need to remember are the two types of cavities- temporary and permanent- and penetration. These will play a part not only in what ammo we shoot, but how we shoot it.

Previous : TOC : Next

At left is a figure showing the typical path of a hollowpoint bullet through ballistic gelatin; a substance used in this sort of testing for its resemblance to human tissues. You can see that shortly after the bullet enters the gelatin, it begins to expand and creates several cavities. The first is the bullet track itself; a hollow tube created by the bullet. Fragments of the bullet also create fragmentation cavities, but these are usually very small. There is increasing evidence, however, that fragmentation damage plays a significant part in wounding potential. A temporary cavity is formed when the shock of the bullet entering the material forces a large stretched cavity that rebounds shortly after the projectile passes through. The permanent cavity is the hollow space that was once filled with material that the bullet has disintegrated with its passage. There is also a shock wave transmitted through the body from the bullet.

At left is a figure showing the typical path of a hollowpoint bullet through ballistic gelatin; a substance used in this sort of testing for its resemblance to human tissues. You can see that shortly after the bullet enters the gelatin, it begins to expand and creates several cavities. The first is the bullet track itself; a hollow tube created by the bullet. Fragments of the bullet also create fragmentation cavities, but these are usually very small. There is increasing evidence, however, that fragmentation damage plays a significant part in wounding potential. A temporary cavity is formed when the shock of the bullet entering the material forces a large stretched cavity that rebounds shortly after the projectile passes through. The permanent cavity is the hollow space that was once filled with material that the bullet has disintegrated with its passage. There is also a shock wave transmitted through the body from the bullet.